The storytelling in set designing

An imaginary world becomes real

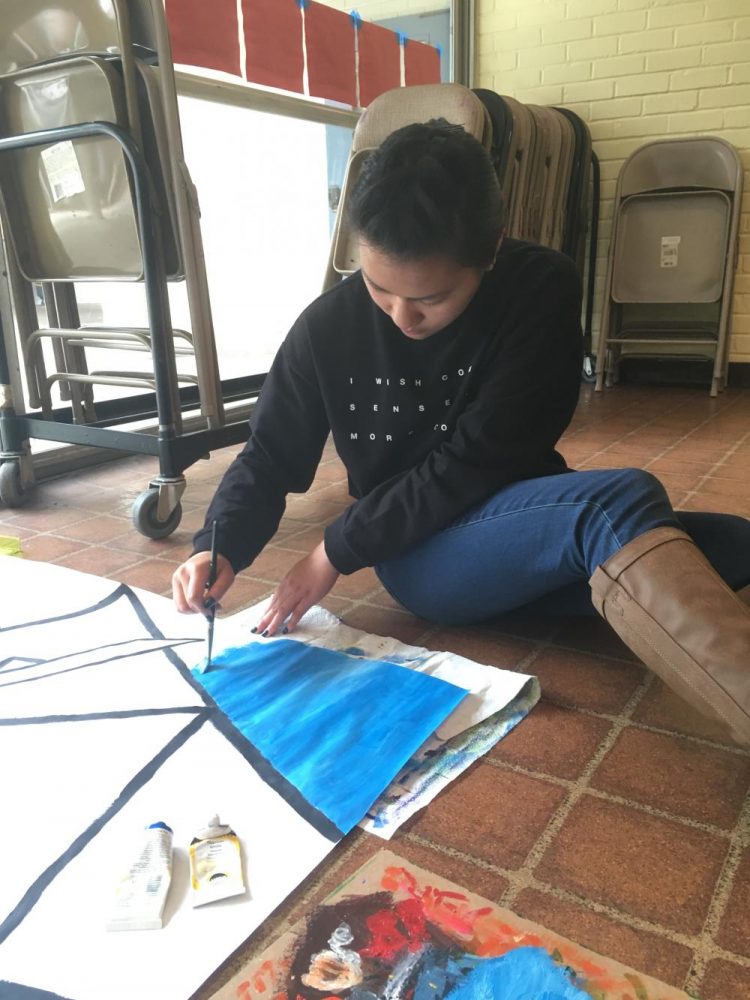

Set building gave me the opportunity to practice my painting skills.

For every musical, much effort is put into training actors and actresses to play their roles as naturally as possible; however, it takes just as much time and effort creating settings and backgrounds meant to reflect the emotions of each scene. This past spring, First Lutheran School in Glendale was planning a musical production to be played by students ranging from kindergarten to eighth grade for Beauty and the Beast, and I joined the set design team to get a better understanding of what it’s like to design stages for a living and what it takes to put a live musical into action.

According to allp, about 8,510 Americans work as set designers, having an average hourly wage of $27.69 and annual salary of about $57,600 (Bureau of Labor Statistics). Educational requirements include a degree in fine art, interior decorating, or performance; however, more experienced set designers benefit more with higher salaries (The Art Career Project).

The role of the set designer is to collaborate and coordinate with technical directors, visual artists, production managers and prop masters to make a story come to life on stage. They overlook every process of construction, making sure that everything is going as planned and that every piece stays consistent with the theme. Set design can also lead to other career pathways including art director, fashion designer, industrial designer or even landscape architect; as a result, going into set design opens up many more interesting career options.

Vignale teaching me how to precisely cut wood.

Burbank resident Rolf Darbo has been a volunteer set designer for about 35 years and has worked on community theater productions such as Barefoot in the Park, Mary Mary, Star-Spangled Girl and High Spirits. Darbo said that set design takes place earlier in the process because it is important that designs properly fit to the exact size of the stage and that they stay proportionate to the props being used.

It turned out that the set design “team” I was part of consisted of only me and my long-time art mentor Joanna Fodczuk, who has taught Fine Arts at First Lutheran for about 15 years and has always assumed the role of solo set designer for every year the school has held a musical. She wasted no time as the first day I joined the team I was required to do extensive research, comparing the original Disney cartoon movie of Beauty and the Beast to live musicals that have been done in the past.

The purpose of researching first was to gather knowledge and inspiration of the story being told so that we would be able to put it onto paper and then eventually onto a makeshift wall as a stage set. Fodczuk said that researching Beauty and the Beast ensured that we do not narrow our vision because we wanted to be open to the many approaches in designing the set. “We can understand Beauty and Beast as a Disney story [from researching]…It is very important to know the whole story, what it came to be, and how the whole story came to life,” Fodczuk said.

The school stage was located within the chapel measuring about 20 feet from one side to the other. With that big of a stage, space was limited, so we had to create portable backgrounds to make it easier to change between different scenes. In addition, the stage and the chapel itself was empty and colorless so we made sure to add vibrant colors and designs for each scene being made.

Fodczuk discussed the design plans with the Principal Michelle Goetsch since she was directing the musical and her approval was needed in order to continue the design process. “[This is] a very important step because [Goetsch] did her own research, and as the main director, she is the boss so she needs to tell her vision and how she understands the play,” Fodczuk said.

According to Darbo, in addition to determining the measurements of the design, other responsibilities of a set designer include the color theme and furniture type of the production. I was responsible for measuring and designing four panels, each about seven by three feet, which made up the French village where Belle grew up. The school had always used these panels as background supports in previous musicals because it was convenient to draw the design on paper and then stick it onto the panel instead of painting on the actual panel itself; as a result, the school is able to reuse the panels for future musicals.

My painting of the forbidden rose as a stained glass window.

We dealt with the village first since it would play a significant role in the beginning scenes of the musical. Additionally, I took charge for one of the stained glass windows, designing it to resemble the forbidden rose that Beauty and the Beast is usually associated with.

After design came set construction which involved constructing props and furniture pieces required for the production. The construction process gave the ability to create three-dimensional components which would later make the stage setting more realistic for the audience. Darbo said that even as a design editor, he participated in set construction under the master carpenter who made sure that the construction process accurately followed the set designs.

I participated in constructing the shelves of the castle’s grand library despite the fact that I had no prior knowledge in construction. Our set construction manager was Frankie Vignale, who has had many years of experience in the field of construction and had also taken part in set construction for other musicals held by First Lutheran. When it came to measuring, we took into account the heights of the students in comparison to the height of the actual furniture piece. Vignale said that the overall look and proportions are the most important factors to consider in set construction since every piece is not scaled to its size in real life. “We have to consider things in relation to the set, how big the stage is, and also what the director is asking,” Vignale said.

Vignale taught other volunteers and me skills and gave tips on how to use certain tools necessary to make the shelves such as the nail gun and the power tool. We had to pay attention to every detail and stay as precise as possible otherwise the shelves would not be able to hold its own weight properly. Measurements had to be exact and the lumber that was used had to be light so moving backgrounds wouldn’t be difficult during performances.

Other pieces made included a fountain, a bed, chairs, trees, book cases, some minor decorational pieces, as well as the invention of Belle’s father, Maurice. Once construction ended, the sets were almost completed with the exception of a few paintings and refinements left to do; the musical was ready for show on May 12.

All our hard work was put to the test on show day. Fodczuk said that she was very pleased and loved the overall look on the stage despite the fact that there were some minor issues throughout the production.

She said that the time between moving pieces was a little too long and it dragged the performance as a result. One example was the bookcase which was composed of three big pieces. The weight and size of these pieces were too much to handle and so we decided to cut the bookcase down to two pieces last minute even though it was not as spectacular as the three-piece bookcase. Fodczuk said that she would have made the construction pieces lighter so that it would be more convenient to move around the stage; and additionally, she would have made a budget so that the school would be able to rent furniture pieces instead of taking the time to construct the pieces.

Fodczuk said that all the time and energy dedicated to making this set was excessive for just one, two-hour play. “This was the most ambitious play we ever did and I’m still resting from it,” Fodczuk said. “We worked to the last minute but everything went well. [Seeing] the children participating and loving it was a huge reward.”

Hobbies/Interests: photography, scrapbooking, traveling

Favorite Movie: Maleficent

Favorite Food: Ice Cream

Plans for the future: living a good life...

Hobbies/Interests: Tear exertion, slumber, dreaming of going to the gym

Favorite Movie: The Lion King

Favorite Food: Chow Mein

Plans for the future: writing...

Hobbies/Interests: Traveling, Hiking, Fashion, Photography, Playing the Ukulele

Spirit animal: Wolf

Places you want to travel to: Greenland, the...