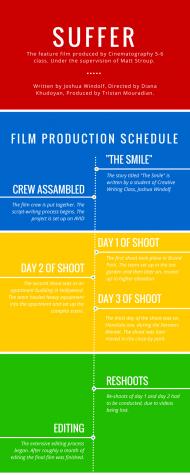

Embracing the magic of filmmaking

Clark students create a capstone film project

The capstone students filming a scene in the Tea Garden in Brand Park. The park was closed due to the shoot, allowing the team to work in silence.

We never truly felt the harshness of filmmaking until the we stood on the hill in Brand Park, under the baking sun, without any protection for a solid two hours. We watched our camera man crawl on his stomach, our actors repeatedly fall down as part of the shot, starved for water, sunburnt and tired. But those are the sacrifices necessary for filmmaking, for the art of cinema.

The art of cinematography is a complex process that requires constant honing of skills. For this reason, often a path into the film world starts as soon as possible. And that is the purpose of the Clark Capstone project: to introduce students to the process of feature filmmaking in high school, allowing them to decide if the process intrigues them.

Nationally, the capstone project, commonly also called the capstone experience, culminating project, or senior exhibition, among many other terms, is a multifaceted assignment that serves as a culminating educational experience. Often given to the student towards the end of their academic career, the project requires the students to tackle an issue unfamiliar to them.

Students conduct research on a subject, maintain a portfolio of findings or results, create a final product demonstrating their learning acquisition or conclusions (a paper, short film, or multimedia presentation, for example), and give an oral presentation on the project to a panel of teachers, experts and community members who collectively evaluate its quality. This is a project that is, according to Association of American Colleges & Universities (AAC&U), present in 268 different 4-year campuses (both high school and college) across the nation. According to the AAC&U, the capstone project allows development of critical thinking, analytical skills, ability to conduct research, career preparation, professional development and proficiency in written communication, among other skills.

The capstone project spearheads a new shift in education towards a more project based learning, according to AAC&U member Jennifer R. Keup. This new system that has been popular as of recent times was most notably demonstrated on April 21, when at the Alex Theater in Glendale, a documentary Most Likely to Succeed was shown. The film highlighted the story of a San Diego high school that focuses solely on project-based learning. The film, shown in an event called “The Future of Education?,” is another indication of the success of capstone projects across the nation.

The shift towards a project-based learning is obvious, as animation teacher John Over noted. “I imagine in the near future the wall between my and [teacher Matt Stroup’s] class will be taken down and we will act as one big class, learning to animate and shoot at the same time,” he said.

However, at Clark, the capstone project only focuses on the cinematography class, while research and presentation of miscellaneous topics is labeled as “Senior Project.” The Clark Capstone requires the Cinema 5-6 class to come together, along with the occasional aid of beginning class members, and form a mock filmmaking crew. The crew acquired short stories written by teacher Maral Guarino’s Creative Writing class, picked their favorite, transformed them into a script, had the script storyboarded, got actors, and proceeded with the actual shoot.

I joined this program straight from my Cinematography 1-2 class. Despite being in Cinematography 3-4 this year, I was allowed to enter the project as a Second Assistant Director. What originally seemed like a nice boost to my grade ended up being one of the most complex challenges in my educational career.

It all started when the project began slightly later than it should have. It was a long and complex journey for the story we got to be turned into an actual script. “The hardest part,” said scriptwriter and author Joshua Windolf, “was dealing with the ideas of another person and having to keep a story with continuity and consistent characters.” After 15 revisions of the script, we were finally close to the production.

Seniors Marcello Marta, Luke Birbedge, and Armand Aloyan are editing the audio of the film. The audio editing was done on a program called Da Vinci.

When the storyboarding was finished by Over’s class, the full production kicked in. The locations were set and the equipment was packaged. “The story we had was very interesting,” Over said. “The most difficult part of it, however, was getting the locations set so that the storyboards will fit the setting.” Over said he was excited about the project and would love in the future to have bigger and more complex collaborative projects with the cinematography classes.

Our first location was Brand Park. We went as far as closing off the entire area for the sake of the shoot. Our actors arrived and we began shooting in the park’s Japanese gardens. As 2nd AD, my role was to move between everyone and make sure that the entire crew was always on point. I was to keep track of all the equipment, aid other crew members, and make sure the members maintained a steady communication between each other.

The shoot got more difficult as we left the gardens and went up the hill into what seemed to be a completely different biome as all the luscious trees suddenly turned into gravel, sand and hellfire. However, the shoot was a relative success, with the exception of having an actual knife dropped on one of the actors’ face.

The second shoot took place in the apartment building of one of the actors, Glen McDougal. After having to haul the equipment up four flights of stairs, along with 400 cans of corn meant to be used as props, we proceeded with another shoot. Of course, no shoot was every perfect. There were arguments and problems. But the most important thing, as cinematographer Marcel Marta said, “is teamwork, and more specifically fulfilling your role in the team.” And through this teamwork another shoot was done.

The third shoot was on Honolulu Blvd., where we had to get to early and shoot the scenes as the crowd slowly built up around us. For a moment I even got to play an extra.

After this, we began editing the film. Up until this point, the project is still going on and will end at the beginning of May. Despite all its difficulties, however, The Capstone is still an impressive and very useful project. “It’s a great way to see if filmmaking is right for you,” said senior Paul Kellogg, the audio supervisor. “It’s about as close to a professional production as you can get at this level, and it can serve either as a head start or an out if you can’t handle it.”

INTERESTS/HOBBIES: Gaming, Reading, movies.

EXTRACURRICULAR ACTIVITIES: KATS, Mock Trial.

THREE WORDS TO DESCRIBE ME ARE: I killed someone.

IN...