War on encryption is dangerous

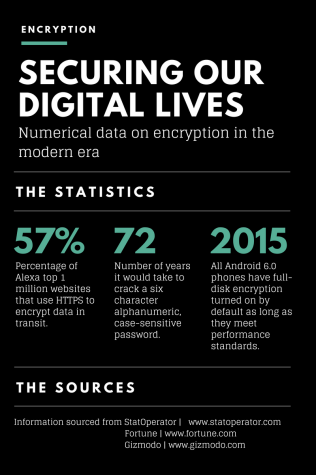

The debate over encryption has been going on since the dawn of the Internet and seemingly exploded in 2016 when Syed Farook and Tashfeen Malik perpetrated a mass shooting in San Bernardino in Dec. 2015. The FBI demanded that Apple produce and digitally sign iOS software which would allow the agency to unlock an iPhone 5C belonging to one of the shooters.

Full disk encryption has been enabled by default on iPhones since the 3GS model and was made even more secure on iOS 8. It makes all of the contents on a device unreadable when powered off and requires a correct password to be entered in order to decrypt the device.

As technology has grown we have placed more and more of our private data onto our smartphones in the hopes that it remains private. Many individuals believe that people should not worry about the government having access to their data, as having “nothing to hide” means having “nothing to fear.”

The problem arises when governments demand that encryption on devices be impossible to crack to everyone but them. The truth is that there is no such thing as “responsible encryption” — if there is a way to crack it then it will be found and exploited.

Leaks are not 100 percent preventable. If there is a backdoor to a system then it will be found and leaked eventually. It is not a matter of if, but when. The government likes to point out that criminals will not be caught and prosecuted if everyone has encryption. However, if we take encryption away from everyone, then only criminals will have encryption. Not only that, but criminals will be the ones who leak the keys to these devices and gain access to everyone’s information if a backdoor is put in place. Thus, it truly is in our best interest for everyone to have encryption.

Take the recent demands from U.K. Home Secretary Amber Rudd for WhatsApp to provide the U.K. government a way to access messages which are encrypted by default. Criminals would simply move to another encrypted messaging app or make their own! In this scenario, law-abiding individuals would no longer be able to chat in secret but criminals still would.

What if, hypothetically, there were no encrypted messaging apps and the criminals were unable to make their own? That would not be a problem at all for them since anyone can simply take a pad of paper and make what is called a one-time-pad. If used correctly, this form of encryption is unbreakable. The same cannot be said about encryption which uses computers.

Politicians who propose encryption backdoors are either uninformed or, quite frankly, do not care about the consequences. It is up to us to advocate for unbreakable encryption so that all of us can have the security which criminals already enjoy.

Hobbies: Playing the electric guitar, going on Reddit

Favorite shows: The Office

Places you want to travel to: San Francisco, Mexico, Canada, Norway

Items...