Fighting for change in diaspora and Artsakh

Here, we see many Armenians protesting for the United States to get involved in the Artsakh-Azerbaijan conflict.

On Sept. 27, Armenians all around the world had their hearts shattered to hear the news that Azerbaijan had bombed Stepanakert, the capital of the Republic of Artsakh, or better known as Nagorno-Karabakh.

“When I heard about the first bombings in Tavush, my heart shattered,” said sophomore Milen Ghukasyan. “Exactly that day, a year ago, I had gone to the same village that was bombed and volunteered at a public park that was opening its pool to the children. I had one thought in my mind on a continuous loop, ‘What if I had gone this year?’ It really opened my eyes and put things into perspective.”

Since the end of September, thousands of protestors have lined the California streets, calling for peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Sunset Boulevard, the Armenian Embassy, the ABC7 building in Los Angeles have been some of the hotspots for many protests. On Oct. 4, there was a large protest on Artsakh Street in Glendale where Armenian rap star Armenchik performed.

These protests have been to encourage the media to give Artsakh increased press coverage.

For years, there has been conflict between Azeris and Armenians because of the small territory that is the Republic of Artsakh. In 1994, war erupted between the two countries, which resulted in an eventual ceasefire, and Armenia regained the land that Azerbaijan has launched attacks over today. Tensions have continued to flare up in armed conflict since 1994, though the recent events have been among the most deadly since 1994.

The most recent conflict began on July 17, but the day of true escalation was Sept. 27. That day, the Azeris bombed a village on the border of Azerbaijan and Armenia known as Tavush. Zartonk media reported about the bombings.

On Oct. 5, in a successful attempt to get more media coverage, many Armenian protestors blocked the 101 Freeway.

Two weekends ago, there was a march from Pan Pacific Park all the way to the Turkish consulate on Wilshire blvd in Beverly Hills, CA. KTLA News reported over 150,000 people in attendance.

“It was really eye opening and emotional, mainly because of how many people were in attendance. I let that thought sink in and I had goosebumps,” said Clark student and protest attendee Inna Arshakyan. “It made me so proud to see my people united as one, and I hope that we stay united.”

A video went viral on another social media platform, Tiktok, when two protestors asked the man sitting in the ABC7LA van why he wasn’t recording or filming them. The two proceeded to call his supervisor, and she reassured them they got their air time, but the two protestors doubted that, at a different protest at the CNN building a few days later.

Many furious Armenians took to various social media platforms to express their pain. The issue with posting about certain events on social media is because sometimes social media platforms take down these posts because they violate their community guidelines. Or, whenever an Armenian commented on an offensive post against Armenia posted by an Azeri soldier, the commenter would look back on the post to find the comments deleted, according to many users on Instagram.

In one such instance, sophomore Meri Hakopyan commented on an offensive post posted on Instagram, but then went to find the comment deleted, but the post was still on the app.

“I wondered why my comments were deleted, and when I looked back on the post, every single comment promoting peace in Armenia was deleted, but the picture of an Azeri soldier standing on top of the Armenian flag was still on the page itself,” Hakopyan said. “I always knew that social media only makes you see what they want you to see, but I didn’t think that it would be that bad.”

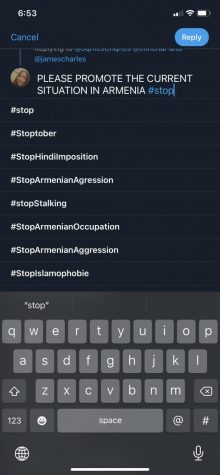

On Twitter, if one would want to use a hashtag #StopAzeriAggression, instead of that one first coming up, other hashtags such as #StopArmenianAggression, or #StopArmenianOccupation would come up in its place as an autofill.

According to Zartonk Media, Azeris have commenced a cyber attack on all Armenian software, but failed when the Armenians fired back, sending them their own cyber attack.

Recently, both Azeris and Armenians have called for a ceasefire, and while Russians attempted to broker peace talks two weeks ago, these talks broke down and fighting continued. News of a second ceasefire erupted on Oct. 16, where France and the U.S. signed a joint statement with Russia, calling for a second ceasefire. However, that ceasefire was soon violated.

“I think that [the ceasefire] is only going to put a pause on the actual issue at hand, and then when the world seems to turn its face again, they will attack again, and this is only a temporary solution to a much larger issue,” said junior Serineh Hayrapetyan.

To raise money to send to Armenian soldiers, many local Armenian businesses such as NOVA Market, Big Square and Byblos Mediterranean Bakery and Pizza have set up donation specials. Other Armenian businesses have been donating all their proceeds to ArmeniaFund, a nonprofit organization that supports Armenia during times of need.

However, the Azeris tried to make profit by creating a fake ArmeniaFund website for people to donate to, and many Instagram pages brought awareness to the recent attack on Artsakh.

Interests/hobbies? I love playing volleyball, listening to The Weeknd, reading, and watching F1.

Dream Destination? All the F1 tracks/circuits

In...