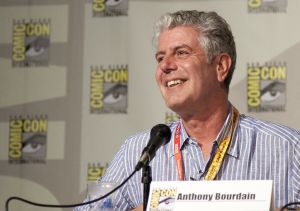

“Food is a reflection, maybe the most direct and obvious reflection of who we are, where we come from, what we love, who eats in the country, who does.” — Anthony Bourdain, American chef and author.

Whether at the forefront of the mind or not, it is essential to recognize that food—like many other aspects of life—extends far beyond the surface level. Food, as Bourdain describes it, is the very foundation of who a person is. It combines vibrant history and values that are then tastefully combined into various dishes.

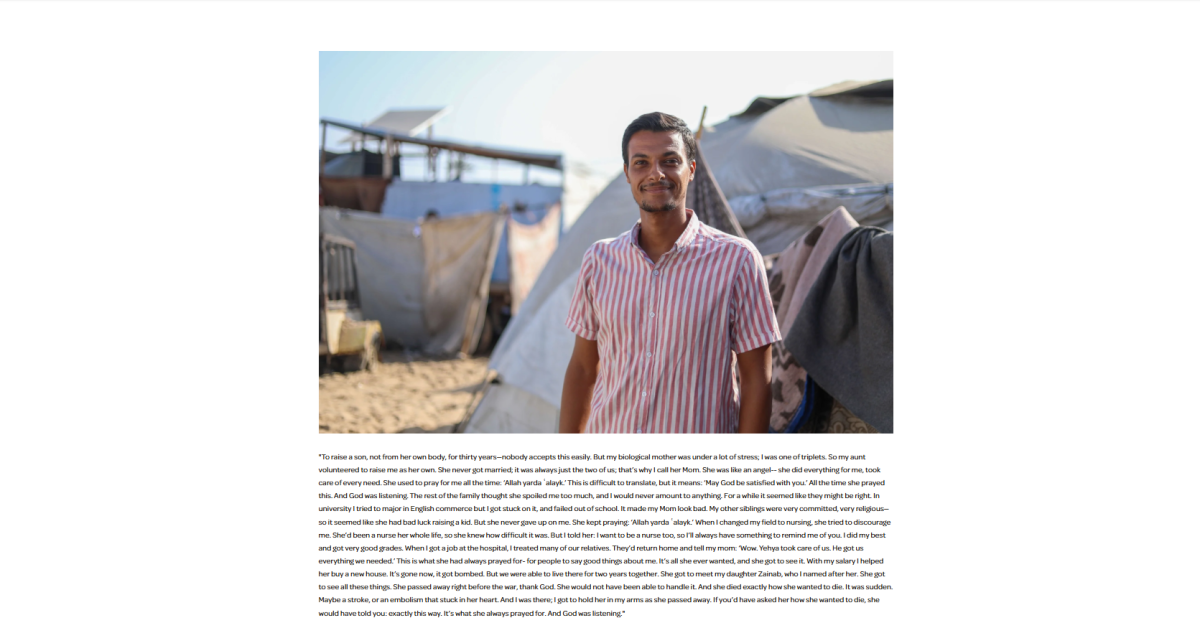

Beyond what lies on the palate, food is often used as a symbol of resistance. In the wake of heightened globalization (building bridges between the world’s cultures, businesses, etc.), a need to revive pre-colonial recipes has arisen.

For one, Armenian dishes were often being replaced with Russian ones.“During Soviet Union control over Armenia, traditional meals became heavily influenced by Soviet culture,” Armenian teacher, Mrs. Nina Minasyan said. Now, instead of Manti (a dumpling-style dish), Armenians were eating Pilmeni, a similar dish introduced during this era of governance. Armenian elders in rural villages continue to make an active effort to preserve original recipes, those without traces of foreign influence.

Looking back, meals have worked as a key identifier of a culture’s struggle and major events. In South Asian cuisine, rice is one of the biggest components of every meal, and that isn’t just because of climate contributions. While it is true that the weather conditions in most South Asian countries help produce rice at a higher level, there is a deeper reason as to why this staple first came about.

As a direct result of British colonization, South Asians faced intense economic struggle and famine, which was then tied to the use of a cheap and easily grown grain— rice. Rice can sustain hunger for long periods of time, and doesn’t pose the risk of easily rotting; thus, a prominent indicator of South Asian culture was born.

Beyond historical facts, food has made its place on the modern scene as well. The influence that food has online has expanded significantly, with influencers even curating their entire online persona to produce food-related content. This content varies from showcasing recipes, restaurant reviews, to videos of people eating the meals they made (mukbangs).

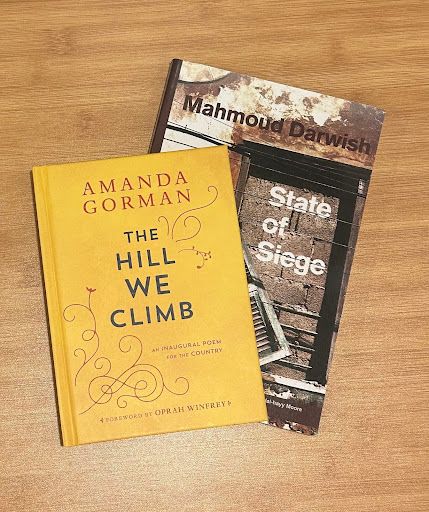

But take a moment to step away from the screen as well. Arguably one of the most striking powers that food has overall, is the ability to connect. This on its own, constitutes its main purpose: making itself apparent in the simple moments; sharing dates during iftar (a meal Muslims use to break their fast during the month of Ramadan), breaking bread during a congregation, or simply sharing a meal with family, all while conversations begin to pass into memories.

Food is a meaningful tool. It’s used to protest, to acknowledge, and to express those intangible messages that lie on the tip of the tongue. It’s the potent way that food is able to inspire emotions of empathy, curiosity, and love that makes every dish, every ingredient, so much more than just a meal.