The dreaded poetry unit. No matter what English classes are taken throughout someone’s academic career, it’s almost predestined that there will be a poetry unit of some sort. From confessional poet Sylvia Plath to the stylistic poems of Emily Dickinson, poetry can be very daunting at first glance. Oftentimes, poetry can even be boring to most students. But this form of literature shouldn’t be treated that way; there are techniques and skills that can be developed over time to help finally conquer that seemingly pesky poetry unit.

First, practice reading some poetry. Look beyond the windows of the Clark English classrooms, and go out and read poetry. The first step to accomplishing anything—be it a great feat of literary achievement, or just striving to get an A on that next found poem assignment— is to make the effort to understand.

For some students, poetry just isn’t something that they can get used to, but that shouldn’t lead to the immediate “I hate poetry” mindset. On the other hand, the genre is worth exploring, especially outside the context of school assignments. Poetry can help put the intangibles into a more digestible format. It also allows its writer to be as expressive and creative as possible, especially with the various forms available.

For those struggling to find some likeable poetry, here’s how to beat that feeling of dread: start with something simple. Preferably, don’t start by reading complex works of “literary merit” within the first shot at the genre. That’s something to work towards for later. Go ahead and take poetry about topics of interest: nature, the structure of society, cultures, or history. Poetry has been, and always will be, diverse. There’s a poem out there that fits an agenda, just go and find it!

There are also several different forms of poetry to explore. The fun thing about poetry is that it’s one of the most flexible forms of writing available. There’s poetry that varies in length, that has a fixed structure, or that follows virtually no rules at all (hooray for free verse!).

Some popular free verse poets to look into are Walt Whitman and E.E. Cummings. Whitman, known as the father of free verse, explores themes of natural identities and transcendentalism. E.E. Cummings was known for exploring and breaking all the rules of formal poetry, a fun style worth exploring. With these poets, the doors open for more expansive poetry than what is seen as “conventional.”

But if poetry can be something as stylistic as that of E.E. Cummings, then where is the line drawn between creative freedom and technicality? It’s in questions like this where the beauty of poetry lies; poetry is meant to test and bend any limitations that are set by others, and that’s exactly why these unconventional works can thrive.

As an extra tip, start with shorter poems and work upwards to the larger, more complicated ones as time goes by, and poetry becomes more predictable in its eccentricity. When finally coming to understand one form of poetry, move on to something that didn’t make as much sense before, take a shot at it now that there’s experience under that literary belt!

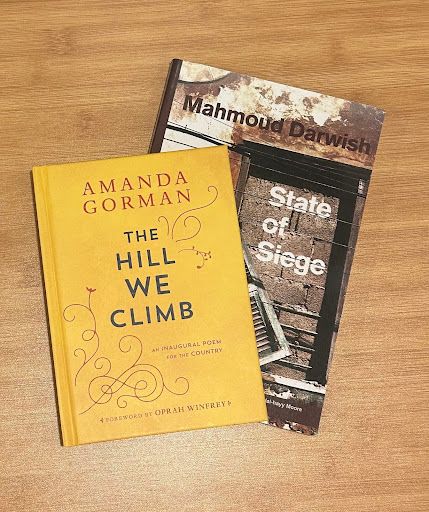

Read poetry from a range of time periods—modern, Victorian, Beat poems (and so, so many more)— and then find a personally interesting era. If none of the older works suit the palate, there are plenty of modern poets who use language that is easy to understand. One of the great poets of our time is the inaugural poet, Amanda Gorman.

Gorman presented her most popular poem at President Biden’s 2020 inauguration. Gorman’s poem is titled “The Hill We Climb” and is packed with a series of political calls to action, striking imagery, and most importantly, comprehensible diction. Gorman, along with a handful of other poets, speaks on the times of now, and what exactly we need to draw our attention to as a society.

“The hardest part of the poetry unit for me is that the language is complicated to understand, especially with figurative language,” senior Maya Fawaz said. There are a few general items to keep in mind when analyzing any work, but especially poetry. Consider the following literary devices: repetition, symbolism, allusion (references to other known texts or documents), and figurative language. Becoming familiar with literary devices can help develop skills to identify and later understand them.

Making a mental checklist whilst reading a poem helps the brain to actively search for those elements, which can later be used to come to conclusions about the chosen poem. Understanding poetry is like being able to finally master cooking a dish, learning how to play a new sport, or practicing a new language. There are steps to take, building blocks to stack. When fully grasping the smaller details (like literary devices), poetry can become like second nature.

With this, good luck with completing a future (or maybe even current) poetry unit! Nothing is ever nearly as hard as it first seems to be; everything just takes a bit of practice, dedication, and most importantly, the willingness to try and understand something new.