Sexed out of sex-ed

Are sexual education classes preparing teens enough for the real world?

December 5, 2016

“Whatever we learned in health class didn’t prepare me for sex at all. It was useless. They teach abstinence, telling us not to have sex until it’s time. But then they don’t tell us what to do when that time comes,” said a Clark senior who did not wish to be named.

This student’s comment about lack of education on sex translates to often unsafe sexual practices among teens. In 2015, a survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicated that 41 percent of all high school students claimed to have had sex, with 30 percent claiming to have had sex within the previous three months. Of this 30 percent, 43 percent reported to have not used a condom, while another 14 percent reported not using any method to prevent pregnancy during their last sexual encounter.

These survey results show that many teens are not using protection, or any form of contraceptive, were supposed to instruct on in school, as required by many states.

Condoms are a form of protection.

“Teens in the United States are far more likely to give birth than in any other industrialized country in the world.,” according to the US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. And according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Nearly 250,000 babies were born to teen girls aged 15–19 years in 2014.”

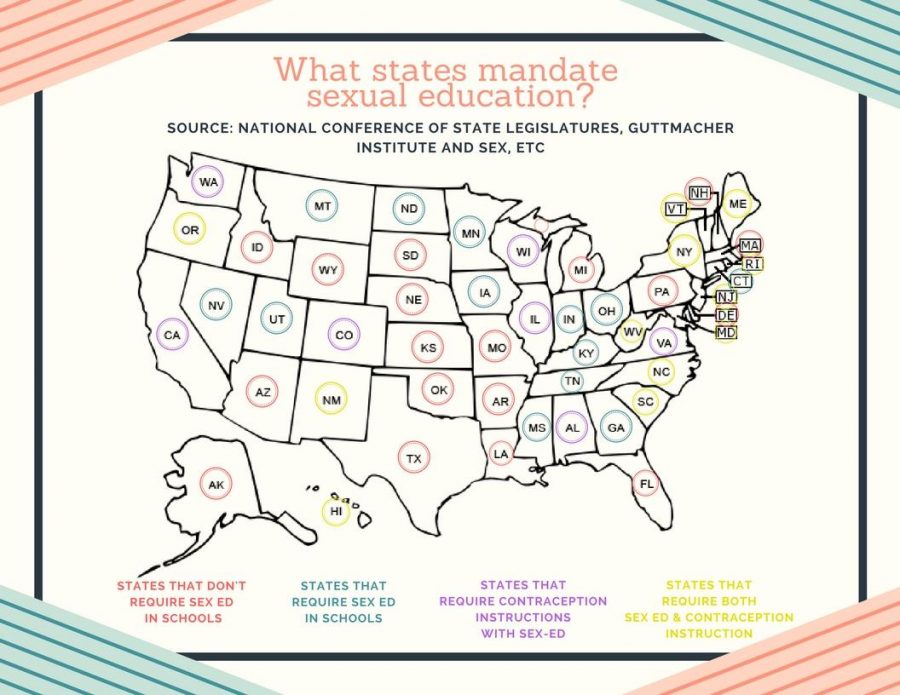

This information may come as a surprise, due to the fact that, according to the National Conference of State Legislators, 24 states along with the District of Columbia have required sex education to be taught in schools since March 1, 2016. Twenty-one of the 24 states have chosen to require sex education and HIV education. There is now a requirement for 33 states and the District of Columbia to inform the students about HIV/AIDS.

Sexual education is required to be taught in schools, yet according to the data showing how many teen pregnancies there are in the United States, along with the information on how few teens use protection, some say that sexual education does not do its job as well as it should. Freshman Vana Hovsepian said, “It we should learn about the health problems from having sex and how to stay safe because at any moment you could be pressured and it’s always a good idea to be prepared.”

At Clark, the freshman class is required to take college preparation for a semester and health for the next. For second semester, during which health in taught, students learn about “Nutrition and Physical Activity; Growth, Development and Sexual Health; Injury Prevention; Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Drugs; Mental, Emotional, and Social Health; and Personal and Community Health,” according to the California Department of Education Comprehensive Sexual Health & HIV/AIDS Instruction.

The health teachers at Clark are required to follow these guideline by providing students with “knowledge and skills necessary to protect his or her sexual and reproductive health from unintended pregnancy and STDs (EC 51930),” and encouraging students to “develop healthy attitudes concerning adolescent growth and development, body image, gender roles, sexual orientation, dating, marriage, and family (EC 51930).”

Condoms are a form of protection.

Based on these guidelines, the message being sent by the California Department of Education is that there are many harms that result from having sexual intercourse, pushing the idea that students should not be having sex. During these lessons, however, students learn about the negative side effects that may result from having sex rather than focusing on instructing students on how to use protection to prevent diseases and pregnancy when the time comes.

Judy Sanzo, one of two health teachers at Clark, said that abstinence in her classroom is more emphasized compared to teaching protected sex and methods of contraceptives. “Students come back to me later and ask me for advice, like when it’s the right time to have sex, rather than asking their parents or friends.”

Breanna Hutchinson is teaching Health and College Prep in her first year at Clark. She believes that students should be well informed on how to use protection. “There are two different sides to sex ed; there’s abstinence, and there’s preventative. You know, being in the teaching world for a few years, it was always abstinence, abstinence, abstinence. That’s great for the kids that do that, but what are you going to do with the kids who don’t do that? You have to teach them the preventative skills, and if you don’t do that, well, sometimes teachers can get in trouble for that. So, you have to [teach how to use protection] because if they don’t know those skills, and that time comes where they’re put in a situation where they do feel comfortable or they don’t feel comfortable, what are they going to do?” Hutchinson said. “They’re (a), probably going to get embarrassed; (b), not know how to put it on correctly, and (c), something might happen that you don’t want to happen.”

There are alternative sources for sexual education beyond formal instruction at school. Teens depend on their parents to answer their questions which may end up being inaccurate and incomplete. They can also depend on their health care provider, which happens during the adolescent’s primary checkup or visit, which may only last up to 36 seconds, according to the Guttmacher Institute. Lastly, teens can turn to digital media to provide them with either accurate or inaccurate information.

“Snapchat is always posting feature stories from Cosmopolitan on sex-related topics, but I never know if I can depend on it,” said senior Cynthia Alejandre.